Vanessa Lamorre-Cargill (E.16) : Language prodigy

Vanessa Lamorre-Cargill (E.16) does not hear quite like most of us. But she turned what could have been a disadvantage into the great opportunity of her life.

Will we be able to have a conversation without an interpreter? Do I need to take a crash course in sign language? Will I need to speak loudly and over-articulate? These are the questions people ask themselves when they are going to meet Vanessa Lamorre-Cargill, who has been hearing impaired since birth. Seated in a café in the Etoile district of Paris on a spring morning, she dismisses these questions with a wave of her hand and declares flat out: “My disability is not a subject.” And yet, that is exactly what we will be talking about over the course of our long, flowing, moving, and warm discussion. Or more precisely, we will talk about the techniques she developed at an early age so that her deafness would not constitute an obstacle to her schooling or her professional career. And her remarkable résumé shows how effective those techniques are!

From the very first minutes of our conversation, I completely forgot that the person sitting in front of me was reading my lips. So much so that I ended some sentences stupidly turning my head down to look in my bag and grab a pen, or turning my head to wave to a waiter at the other end of the room. Even so, it did not interfere with the discussion in the least.

“I’ve developed strategies for finding substitute words in my head. I fill in the missing parts to understand the meaning of the sentence. A bit like when you’re learning a foreign language,” explains the elegant forty-year-old. She has had plenty of experience describing her pathology in the manner of a teacher to lay the foundations for good communication. Language is learned through imitation, repetition. But my hearing is very faint and the frequencies I register are not the same as those perceived by a normal hearing person.” But it would have taken a lot more than that to dissuade this incredibly determined woman from finding her voice!

Champion of dictation

“Since I was a child, I have worked hard to overcome my difference and integrate with society. I used to go to a speech therapist three times a week. I fought hard. I always wanted people to say to themselves: ‘She has made a success of herself. And, by the way, she’s deaf.’” This understandable need not to be reduced to a disability probably acted as a booster. “I always did very well in school. And I never had any special treatment. I did dictations like everyone else.” Of course, she is quick to swallow old feelings of resentment about bad grades from a slightly devious schoolteacher whose pronunciation was a little indistinct!

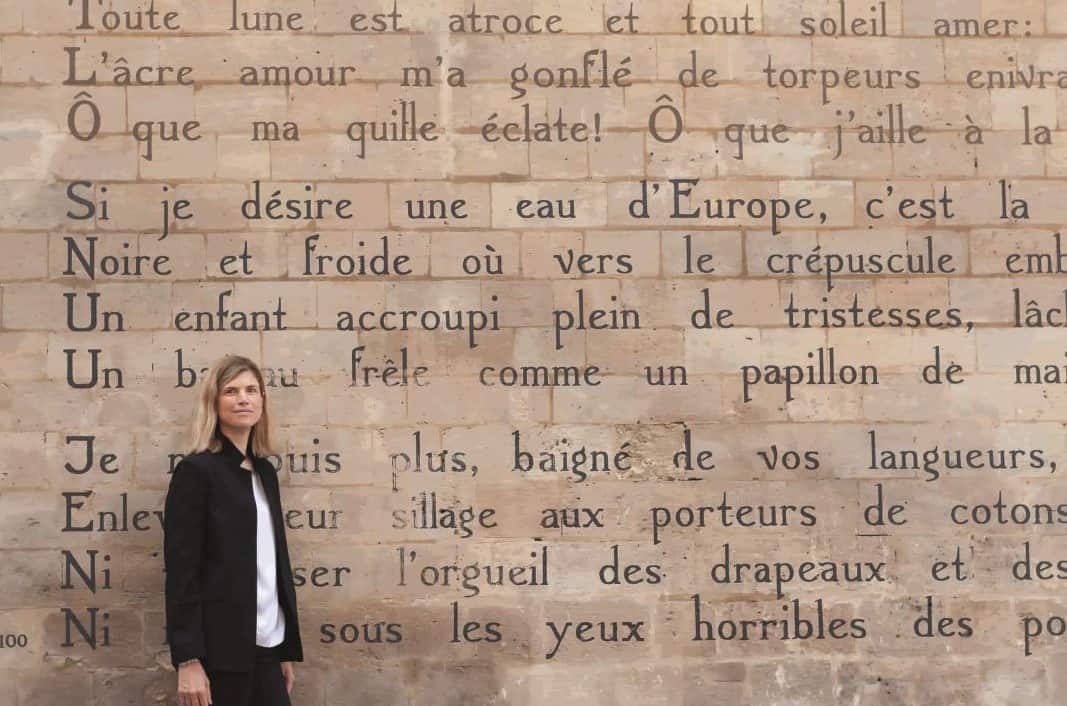

Few adapt their behavior to accommodate her special needs. But Vanessa Cargill fondly recalls one teacher at her Catholic primary school who reorganized the layout of his classroom so that he would no longer have his back to Vanessa while he was writing on the board. “He told me it had changed the way he taught.” After high school, she first set about a master’s degree in art at the University of Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her sister, a HEC graduate, encouraged her to come to the school, which Vanessa did in 2001. “When I took the oral tests in English and Spanish, the examiners were a bit confused and ill at ease. But that soon turned to admiration, because I was a hit! I got 17 out of 20 in the English oral and 19 in the 5 on 5 interview.”

One senses the delicious pleasure she takes in surprising the people she is talking to, flabbergasting them, reversing the roles by leaving them… speechless! In 2003, she took part in an exchange program with the Thunderbird School of Global Management. And she got her master’s degree in business administration and management in 2004. With no special arrangements or exemptions.

A wonderful misfortune

Ten years later, with a wealth of professional experience and a desire to change her path, she returned to HEC to enroll in the Master of Sciences Coaching and Consulting for Change program (with an exchange at Oxford University). She completed it with flying colors in 2016.

She has a steadfast conviction that her difference is not a brake, but a motor. “Things are never just what they are. They are also what you make of them. And boundaries are never what you think they are. We have a great capacity for resilience. You just have to learn how to implement strategies to respond to situations,” she says optimistically, referring to Boris Cyrulnik’s book A Wonderful Misfortune. And that’s what led her to set out on a new path. “Being hard of hearing has allowed me to develop non-verbal language, which is a great strength. That is what led me to do a master’s degree in coaching, to help others overcome their problems.”

She has never given up. When she applies by email and is offered a telephone interview, she suggests a face-to-face meeting, without even mentioning her disability. When she senses that the recruiter is apprehensive, she calmly explains that videoconferencing systems, emails, and text messages allow her to communicate freely.

That is how she was able to prove herself at Goldman Sachs in London, then at CSC in Paris, before being recruited by Sodexo, where she stayed for ten years. In January 2019, she joined Axa, “a company that protects people in the event of hard times, which has a special resonance for my life path.” She notes that her colleagues often forget that she is different. “In recent years, the way companies view people with disabilities has changed. There is more awareness and inclusion,” she says.

Sound and fury

Sometimes, she even thinks of her deafness as an asset: “People with hearing aids or implants can switch them on and off. And it is an advantage to be able to cut off the sound when you want; it lets you come back to a sort of presence in the world. It shields me from pointless conversations where people are just talking for the sake of it. In Macbeth, one of William Shakespeare’s characters declares: “Life is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing”… It’s kind of true! There is always an overabundance of sound input.”

Vanessa Lamorre-Cargill also likes to point out that, contrary to what everyone assumes, she does not speak sign language. The mother of two little boys born in 2016 and 2017, and a board member of the HEC SpiritualitéS Club, she has had a complicated relationship with God throughout her life, especially in her youth.

And she remembers the question she frequently asked her parents in the face of injustice: “Why me?” She often mentions her sister, with whom she seems very close: “She has always been a driver. She would put music on my ears and spur me on until I recognized the songs.” The two sisters lived in London during the same period. Growing up in a family of well-off and attentive hearing people certainly helped her rise to challenges. To compensate for her poor hearing, she has excelled in everything, not just in school and at work. A marathon runner, a mother, and a person of rare kindness and elegance, Vanessa is simply stunning.

Published by Hélène Brunet-Rivaillon