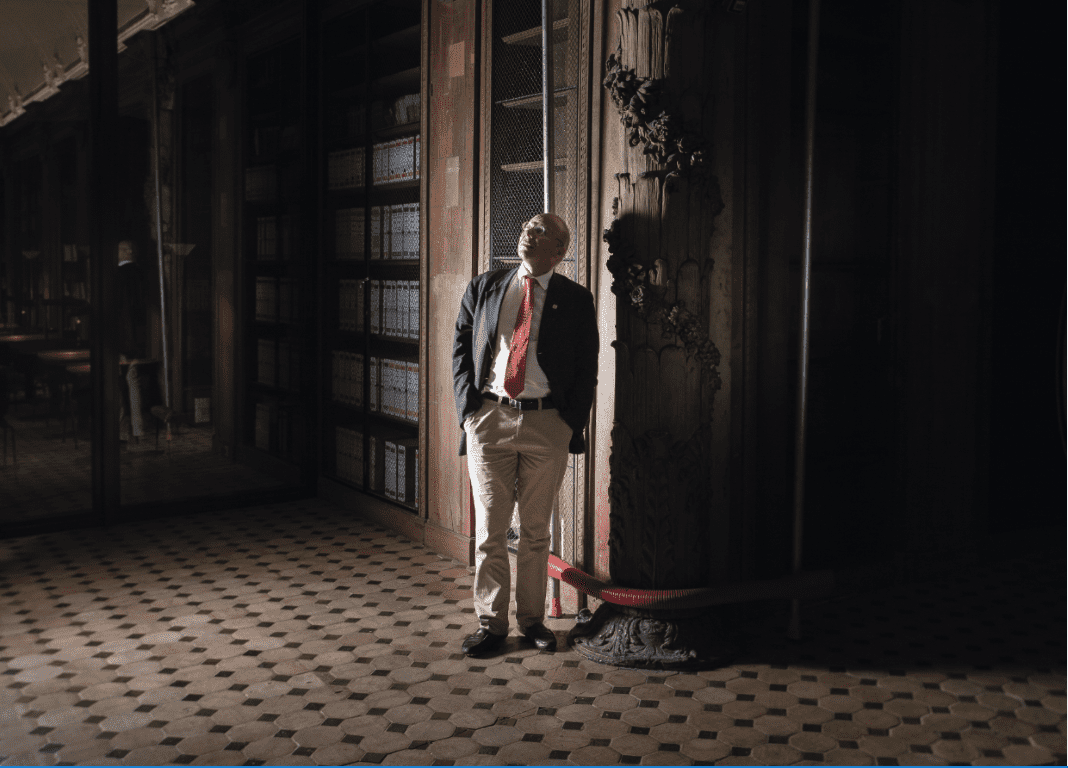

Guillaume Poitrinal : “French patrimony deserves better.”

Last April 15, terrifying images of Notre Dame cathedral in flames circled the globe. It took more than 15 hours to put out the fire, which had started in the cathedral’s roof beams. French people and heritage-lovers from all over the world were profoundly moved, and they began to send in so many donations to finance the building’s reconstruction that some observers were surprised. In fact, patrimony has been growing in popularity for many years. Guillaume Poitrinal (H.89), president of the Fondation du Patrimoine, makes a major contribution to the conservation, restoration and promotion of large and small monuments throughout France. And there is a lot of work to be done.

What brought you to the Fondation du Patrimoine?

Guillaume Poitrinal: I was born in Châtellerault and lived there until I was 16. The Fondation du Patrimoine saved the city’s little Italianesque theatre, built in 1850, and I was a bit involved in raising money for this project. This was my first contact with the foundation. In addition, the Fondation du Patrimoine is usually headed by a former CEO of a CAC 40 company, which was perhaps another reason I was called on to become president in 2017.

After the fire that devastated Notre Dame, were you surprised by the mass movement to support rebuilding the cathedral?

Guillaume Poitrinal: Yes! We were the first to launch a subscription, in reaction to all the funding projects that were being created spontaneously, since there’s always a risk of scams. It’s best for donations — especially those driven by an emotional response – to be collected by an official organization. After such a dramatic and widely reported event, every hour counts: donations start to come in quickly, but this flood of cash is transitory. People soon move on to other things. We wanted to respond to this widespread emotion, and we were overwhelmed. Our Internet servers were saturated, and the next day we had to boost their capacity. We brought in most of our 600 volunteers to handle phone calls, because people not only wanted to give something, but also to talk to someone.

We received thousands and thousands of checks, the whole contents of eight-year-olds’ piggy banks, wire transfers from older people who had emptied out their savings accounts… Offers of services, too: hundreds of craftspeople who dreamed of getting involved in the reconstruction. Everyone wants to build cathedrals. And we even received donations of trees, thousands of them that had been planted by people’s ancestors or that had been part of people’s families and had tremendous symbolic significance. The preservation of monuments really comes into its own at times like this, when we have a responsibility toward people and their history.

What is the total amount of the donations your foundation has received to finance Notre Dame’s reconstruction?

Guillaume Poitrinal: We have received donations from 250,000 individuals for a total of 24 million euros. Added to this are pledges by major contributors (around 30 million euros) and donations from leading corporate benefactors (167 million euros), with which we operate according to legal frameworks. Overall, the total is around 221 million euros. Thanks to the large amount of donations and the exceptional support of some extremely wealthy individuals, we stopped accepting donations after a month and launched the “Never again!” subscription appeal designed to ensure the security of all French heritage properties.

This was sadly not the first tragedy to hit historic French buildings.

Guillaume Poitrinal: It’s true. Every 10 years or so, something terrible happens to one of France’s heritage properties. Think of Lunéville chateau (which has had several fires, the most recent in 2003), Nantes cathedral (partially destroyed during wartime and by a fire in 1972), or Brittany’s parliament building (which burned in 1994). The security of French heritage buildings still leaves a lot to be desired.

This is France’s challenge: we have one of the most beautiful architectural heritages in the world, and we are the worst in Europe at maintaining these properties. Even in a little town undergoing redevelopment, with 30% unemployment and a derelict urban landscape, you can open a door and discover a magnificent 15th century chapel. For a very long time, individual communities were supposed to take care of the maintenance of such things, but they rarely had the means to do so, and neither did districts nor regions, for that matter. That’s why we exist.

Can the generosity of French people make up for this lack of means?

Guillaume Poitrinal: The French have traditionally not been particularly inclined to donate. They think that they pay enough taxes for the government to take on such expenditures. Today, mentalities are changing and there’s a real “reservoir of donations”. I think that the impulse to be generous is self-driven; the more one gives, the more generous one becomes. And this is a good thing, because many causes need our support. People should donate to the Fondation du Patrimoine and the HEC Foundation: equal opportunity is another important cause in our time. I personally donate to these two foundations.

Is there a particular social group that is more sensitive to the issue of patrimony?

Guillaume Poitrinal: At the beginning, this cause mainly touched the upper and middle classes. I think that today, thanks to the national lottery and Stéphane Bern, and with the Notre Dame fire, we are seeing more media coverage of the issue, and this has raised the consciousness of the general public, particularly young people. It’s encouraging!

Are you responsible for launching the patrimony lottery?

Guillaume Poitrinal: Yes, with Stéphane Bern, based on an idea once suggested by François de Mazières, the mayor of Versailles. We met with the French national lottery organization and with the Ministry of Economy and Finance to propose a lottery that would target a new public. This initiative proved to be a big success for the Fondation du Patrimoine, which doubled its revenues in just one year, from 25 million euros to 50 million euros. It was also a plus for the French lottery, which attracted new participants. And, thanks to taxes on winnings, even the Ministry of Economy and Finance came out ahead. In England, a large part of the National Heritage budget comes from the national lottery. The French national lottery was also philanthropic when it began, because it was required to help finance care for people wounded in the war in 1918.

What would be the ideal budget to earmark for monuments and historic buildings?

Guillaume Poitrinal: Working with the Mission Bern, we did a survey of sites in danger and we estimate that we need around two billion euros. To do this properly, we should budget around 300 million euros per year (which corresponds to the amount the British spend each year in maintaining their monuments).

What criteria do you use to decide whether a building is an historic property, one that represents French patrimony?

Guillaume Poitrinal: There’s no set rule. It’s a collaborative effort in which many factors come into play. We take into account the opinions of architects specialized in heritage buildings, and we have discussions with regional cultural organizations. We have to decide whether something is rare, whether it reflects specific esthetic criteria of its time, a style or a school, whether it was built by craftsmen using techniques that no longer exist…. After all these things are studied, a regional commission is established to deliver a verdict.

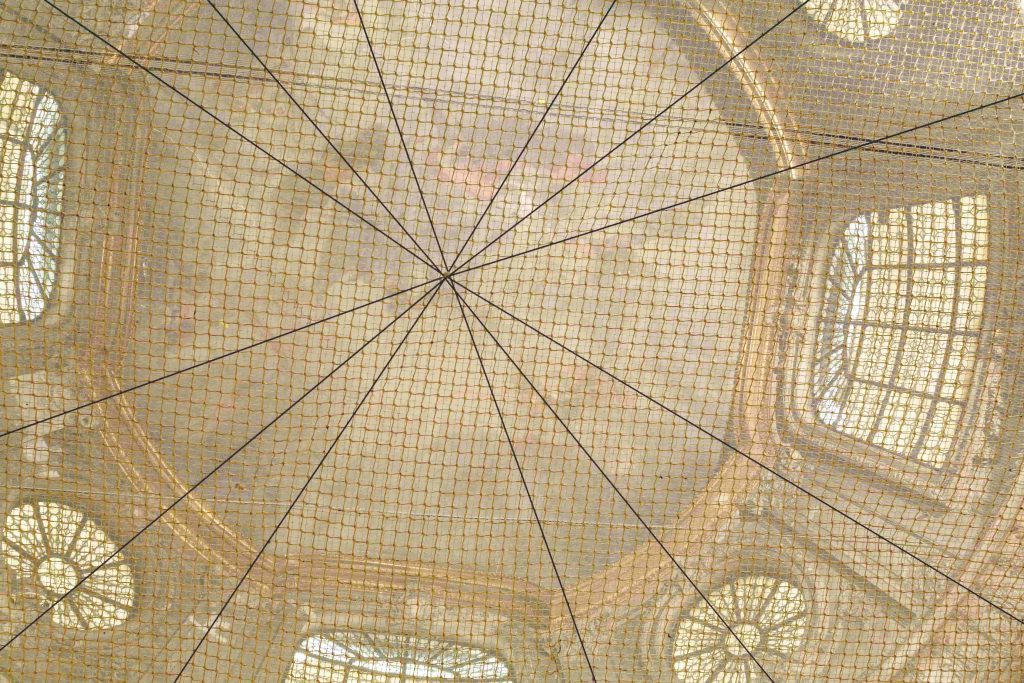

Can digital technologies play a role concerning patrimony?

Guillaume Poitrinal: Of course. And in many different ways. For example, 3D modeling, very common in architecture, can be used to make complex renovation projects possible. This technique was employed to create an impressive reconstitution of Notre Dame’s roof framework. We can also use 3D technology to propose virtual visits of many buildings – in their current state and what they would be like after renovation! People can take such visits online, via the Internet. The Internet is a real revolution, since it makes direct contact with the public possible.

So the foundation has a strong Internet presence?

Guillaume Poitrinal: Yes, we’re active on social networks like Facebook and Twitter. Our web site lists 2,940 renovation projects open to donations by subscription. The great strength of the Internet is to create small communities of people with the same local or thematic interests. Each person can therefore find a renovation project that appeals to him or her individually, for example something that’s a reminder of one’s childhood or one’s family home, or which matches one’s religious convictions, artistic tastes, passions, etc.

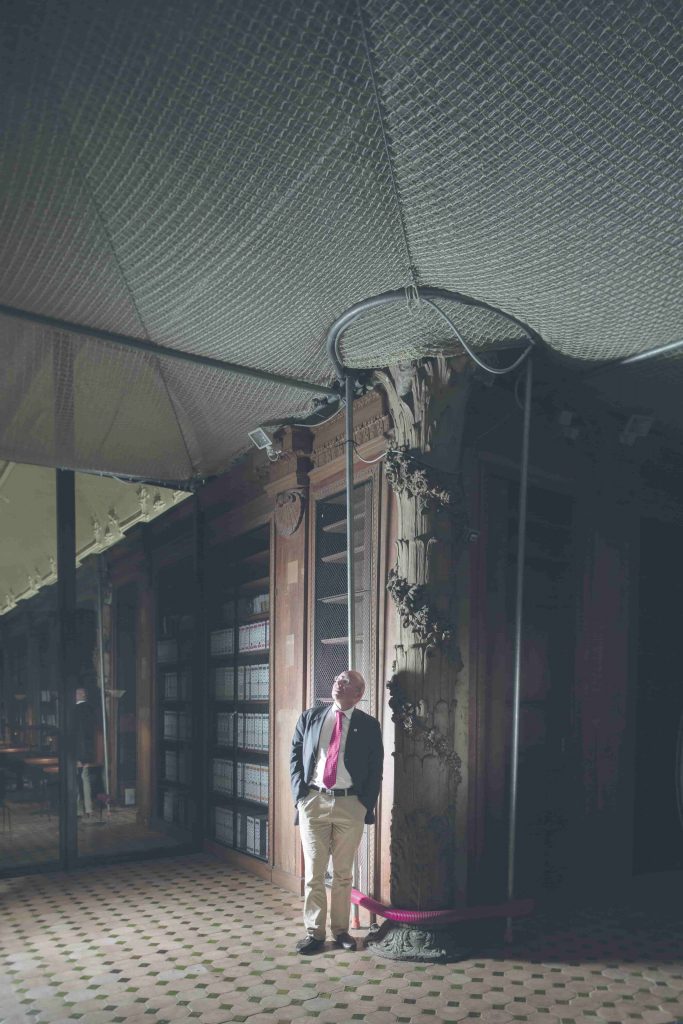

Can monuments have a new life?

Guillaume Poitrinal : I’m not in favor of every 19th century church standing empty. It doesn’t bother me if some of them are deconsecrated to become restaurants, hotels or nightclubs! Such transformations create jobs, since restoration projects involve local labor and companies that train people in marvelous crafts. Maintaining heritage buildings can generate a virtuous circle and a perspective on the future that emphasizes both preservation and transmission.

Published by Hélène Brunet-Rivaillon