For or Against : A special status for climate refugees ?

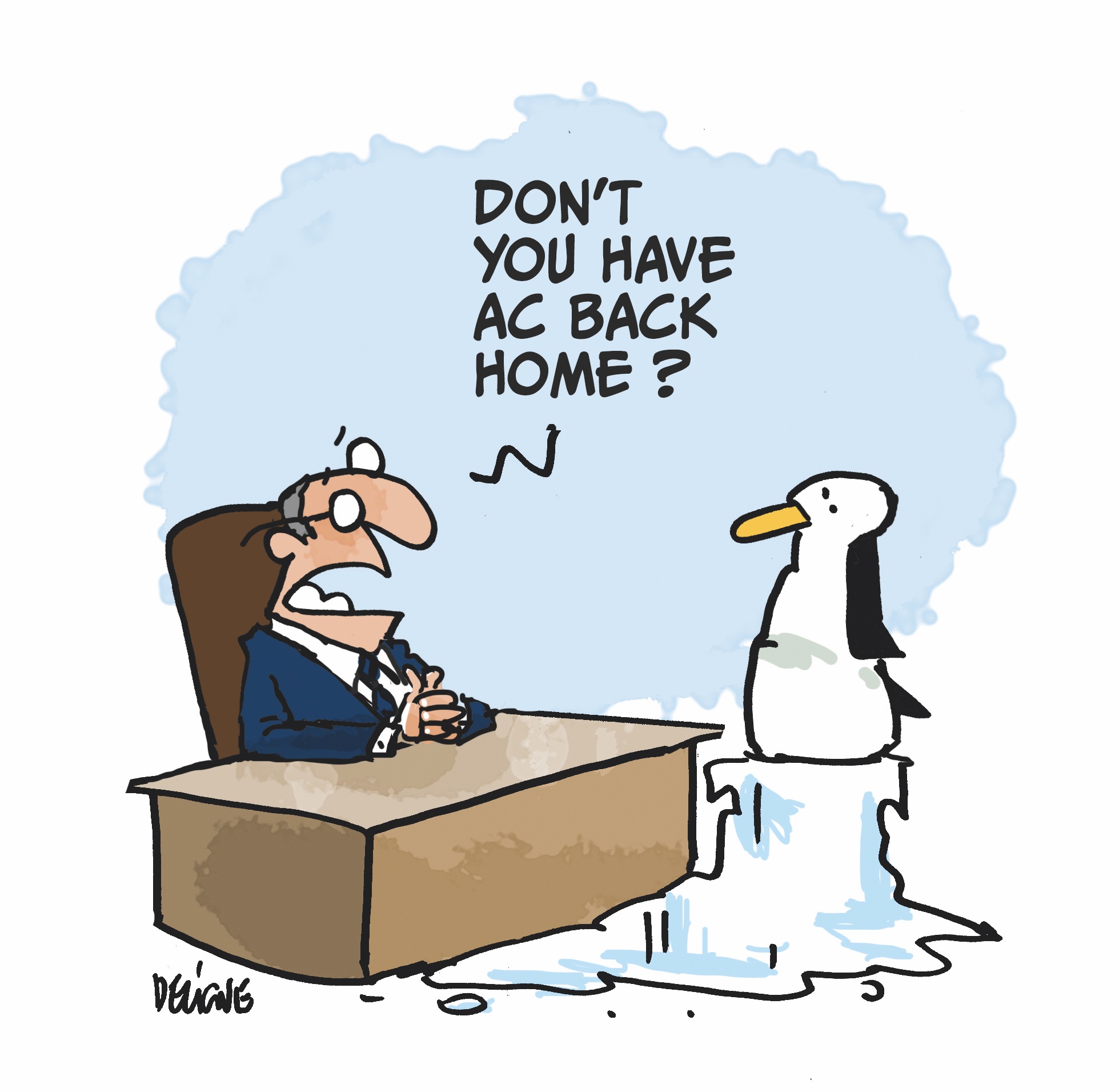

According to the UN, 20 million people are forcibly displaced ever year by to climate-related events. Do we have to protect these migrants at an international level?

For

Bertrand Badré (H.89)

Former managing director and financial director of the World Bank, he fervently defends a “moral capitalism”. He created a sustainable investment fund that he named Blue Like an Orange Sustainable Capital, in tribute to French poet Paul Éluard. Its purpose is to finance projects that can generate a positive impact in emerging countries.

In 2013, an inhabitant of Kiribati, a South Pacific archipelago threatened by rising sea levels, applied in New Zealan for a refugee status due to global warming. A world’s premiere. He was denied, though, and brought a case against the New Zealand government at the UN Human Rights Committee in February 2016. The Committee issued a quite revealing decision: governments must now consider human rights violations caused by the climate crisis when considering deporting asylum seekers. While a framework is not well defined yet, it is clear that the issue is emerging and that climate change will condemn more and more people to migration, either because their environment will be destroyed or because it will be so polluted that they will no longer be able to live there.

Anticipating the effects of global warming

How will we cope with these population shifts? Part of the answer depends on our adaptation strategy: will we be able to put in place decent living conditions so that these people do not become refugees? This is what is at stake in the ecological transition. We are trying to implement solutions by designing more livable and sustainable cities, by building dikes, by restoring mangroves… We will have to think, plan and carry out these initiatives on a local scale, but also on a global scale. If we fail, which is unfortunately very likely, we will have to find answers to the following questions: how can we organize ourselves for the good of the populations concerned, but also for the good of the populations that will host these migrants? How can we ensure that this reality does not become a new source of conflict in the world? Will it be necessary to allow countries to relocate elsewhere and under what conditions?

The Covid crisis has shown us that we find solutions when our backs are against the wall. But we should seriously anticipate this issue. And Europe has a particular responsibility to initiate this reflection. It is the creator and custodian of the current refugee status, and will soon be confronted with a phenomenon unprecedented in the history of humanity.

Against

Emmanuel Daoud

Lawyer and founder of Law firm Vigo, he is involved in international criminal law, human rights, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. He was the lawyer for the “Case of the Century,” a lawsuit filed in March 2019 by four NGOs against the State’s climate inaction.

The 1951 Geneva Convention links the refugee status to the notion of “persecution” as well as the crossing of a border. For these new migrants, displaced by the degradation of their environment, the existing law is therefore inapplicable and insufficient. An evolution of positive law with the creation of a specific status seems necessary. It would allow developed countries to take their share of responsibility in the face of the consequences of global warming. However, it would experience serious difficulties.

The recognition of a specific status for climate refugees requires the creation of a new convention or the addition of a protocol to the 1951 Convention. This would require a consensus among states, as the management of migratory flows is a matter of national sovereignty. However, the notion of “climate refugee” is not unanimously accepted. It has even been described as a legal outlier, the result of a media invention echoed by certain academics. This expression suggests that protection is possible based on international refugee law, which is not the case. Some prefer to use the term “environmental displaced persons”, a more appropriate notion referring to a broader category than “climate refugees” that would be considering “internal and international, forced and voluntary displacements”, as explained by Christel Cournil, professor of public Law.

There are at least two obstacles to the conception and recognition of a climate refugee status. First, the plurality of migration patterns (temporary or permanent, internal or cross-border, planned or precipitated, etc.) and the interweaving of socio-economic factors. A single legal status would not be able to protect all types of climate displaced persons. The second problem is political: the migration issue is very sensitive in Europe, and countries often respond with security measures, sometimes to the detriment of fundamental freedoms.

Achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement first

To provide an appropriate response, it would be better to favor a more pragmatic and immediate solution. The human cost of climate change affects poor countries first. It is essential that developed countries come together to achieve the temperature limitation objectives of the Paris Agreement. If they fail to do so, they will have to take responsibility at a domestic, community and European level.

Published by La rédaction