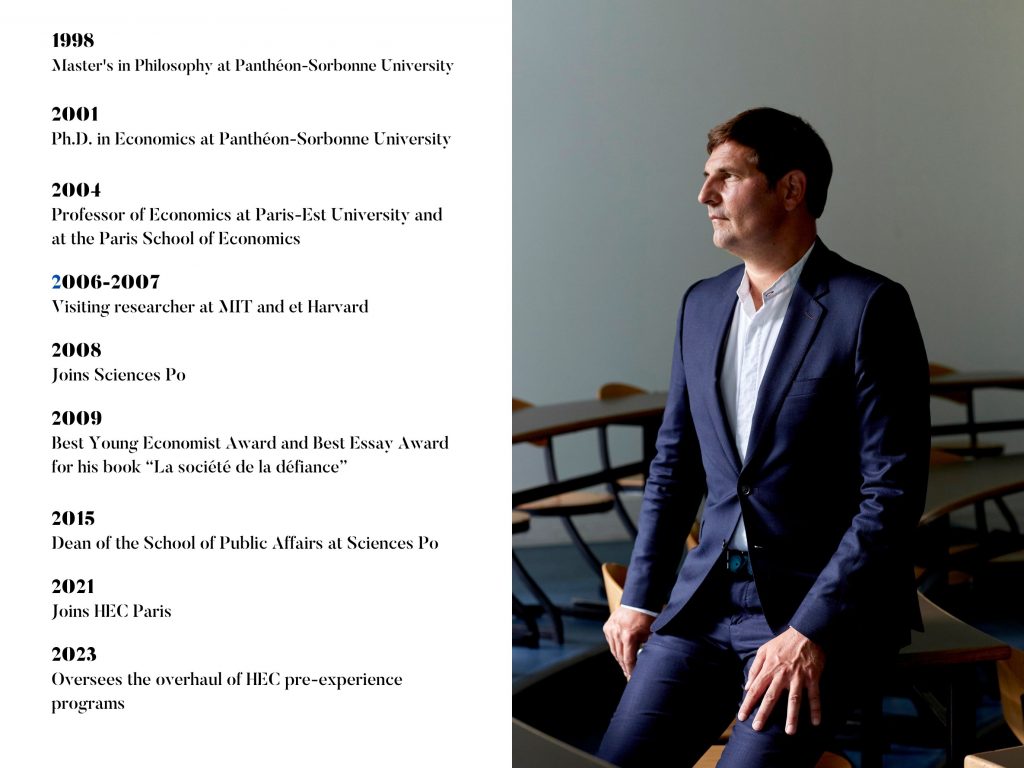

Yann Algan Introduces HEC’s New Courses

The overhaul of the pre-experience programs took effect this September. It had been in the works for two years prior. This is a major step for HEC Paris, who aimed at addressing the ecological and social challenges of our time in a better way. Associate Dean of the Pre-Experience Programs and specialist in the role of trust within organizations, Yann Algan is the economist who orchestrated the transformation of the academic path. He reflects on this significant change.

The academic program of the Grande École is changing. Why and how did this transformation take place ?

Yann Algan: The structure of HEC Paris training programs remained the same for about a decade. It doesn’t mean that nothing was done before. There were many experiments, new courses, and pathways launched… But it seemed important to capitalize on these experiences to systematically reform the curriculum.

As the leading business school in Europe, it was our responsibility, to address the profound environmental, societal, and technological transformations of our time. We don’t just train future leaders; we educate enlightened individuals who will have a significant impact on the world of tomorrow. We need to support them in the best way possible.

The Grande École program is not narrow. Our students don’t just focus on business. Many of them enter the public sector, non-profit organizations, or international organizations. In light of the new programs, I would say that HEC Paris Grande École has become a school at the crossroads of management, social sciences, and data science.

Is this new vision of the school unanimous ?

Y.A. : Y.A.: It took us a year and a half to mobilize the entire ecosystem. The committee of experts that undertook the reform included deans from business schools like Oxford and MIT, CEOs like Ada di Marzo of Bain & Co, public figures like Anne-Marie Idrac (former minister, former president of RATP and SNCF), experts such as Gilles Babinet (co-chair of the National Digital Council), and Marguerite Cazeneuve (H.13, number two of the French Social Health Insurance). And, of course, representatives of our students and alumni. This collective movement allowed us to redefine the narrative of the Grande École.

What is the modus operandi for reforming this program ?

Y.A.: We have defined three levels. The first is to educate our students with an open approach to all kinds of knowledge. It’s about preparing them for the major challenges of the climate transition, as well as societal, technological, and geopolitical transformations.

The second is to provide them with in-depth knowledge of private and public organizations, using a multidisciplinary approach in management sciences, social sciences, and data science. Finally, we train future leaders with a genuine entrepreneurial spirit, which means the ability to provide concrete and innovative solutions.

“After two or three demanding years of preparatory classes focused exclusively on academic knowledge, it is crucial for our students to open up to society and the business world.”

The first pillar involves strengthening students’ general knowledge. How is this reflected in the courses?

Y.A. : The first year (L3), which follows preparatory classes, has been profoundly revised with a more multidisciplinary approach: courses in law, economics and finance, accounting, data analysis, etc. The Master’s cycle (years M1 and M2) is focused on management and the development of a “solution-oriented” mindset through an entrepreneurial journey.

In L3, students will attend a 30-hour course on global issues taught by researcher François Gemenne. Co-author of the sixth IPCC report, he has just been appointed as a professor at HEC, which is excellent news for the school. He will address issues related to the environment and global warming, with the ambition to go beyond analysis and provide tools and solutions.

Moreover, L3 students will be able to choose one major elective course on geopolitics and globalized spaces international relations specialist Bertrand Badie, on artificial intelligence challenges with Gilles Babinet, on human behavior and psychology or on the future of democracy and societal transformations.

First-year students will also have to engage in a very concrete way…

Y.A. : After two or three demanding years of preparatory classes focused exclusively on academic knowledge, it is crucial for our students to open up to society and the business world.

Each student will have to complete 30 hours of civic engagement in social and solidarity economy (SSE) or humanitarian associations, involving concrete field actions such as outreach, food distribution, pollution cleanup, or even tutoring. One afternoon a week will be devoted to this civic engagement path.

Furthermore, their introduction to the business world will begin with a three-week field internship, “getting their hands dirty,” which means without managerial responsibilities and more focused on execution tasks, so that they understand the reality of the working world in all its dimensions. In the second semester, they can still choose to specialize in a university cycle or study abroad. We offer more than fifty destinations at the world’s top universities.

“The accounting courses now include methods to tackle the intangible impact of the company on the environment and society.”

This leads us to the the first year of the Master’s degree (M1)…

Y.A. : The Master in Management program begins in the 2nd year (M1, with 800 students) with a curriculum in management sciences, a data science track, in-depth work on managerial skills (team management, negotiation, leadership), and a choice of more than a hundred elective courses. It will show how companies or the public sector can address the challenges presented in L3.

Management courses have been updated to include ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria. Students will follow traditional HEC courses with a systematic consideration of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) issues: sustainable finance, sustainable logistics, and so on.

Can you give an example?

Y.A. : A “traditional” accounting course only explains how to transmit financial information to shareholders. Following a paradigm shift, our accounting professors also present methodologies to address intangible impact a company can have on the environment and on society (its positive and negative externalities, so to speak), as well as pathways to net-zero carbon.

Another example is the supply chain course. The basic logistics paradigm was to minimize costs and maximize transport flow flexibility. Now, it’s about thinking about supply chains that reduce carbon footprint. We are fortunate to have a world-renowned faculty highly engaged in these issues. In the last three years, 40% of our researchers’ publications were on ESG topics. I would add that in business, our young people will have the heavy task of creating consensus, engaging teams, negotiating, and managing crises. We will offer M1 students many workshops on these soft skills.

In the second semester, they will follow an “entrepreneurial mindset” path, where they will work on challenges posed to a company, a government agency, or an NGO. They will have a semester to go from ideation to prototyping.

In broad strokes, what proportion of the Grande École program has changed with this reform ?

Y.A. : I would say more than half of the L3 and M1 years. We will begin a reflection on the M2 year dedicated to specializations in the next school year. Of course, some fundamental skills will still be taught as before but applied to contemporary issues with significantly updated case studies.

Did you encounter any reluctance or obstacles in this program reform?

Y.A. : Frankly, no. However, we had to think about how to integrate all these new dimensions into the courses. Our teaching staff is not satisfied with just a facelift but is thinking about paradigm shifts. This demonstrates HEC’s commitment to investing in research related to teaching. The whole exercise was to create common spaces for discussion among the various departments.

Have professors received a bonus or compensation for their contribution to this new curriculum ?

Y.A. : No bonuses, no. The cost of implementing this reform was high, to be sure. But our teachers have a passion for knowledge and education. They are committed to renewing their research and teaching. This will lead to experiments and assessments to correct what doesn’t work and strengthen what does work. Let’s be humble, we are only at the beginning of the road, facing extremely complex challenges.

Last year, students at the campus disrupted a climate roundtable attended by employees of Société Générale, Shell, and TotalEnergies. The French energy company had also been challenged at a recruitment forum. HEC aims to prepare responsible leaders of the future. Should it ban certain sponsors if their policies are inconsistent with the Paris Agreement?

Y.A. : Students are obviously at the heart of HEC’s project and have participated in the reform. However, our responsibility for the success of the energy transition is to have all the major players at the table. A graduate who shifts TotalEnergies’ trajectory in the right direction by 1% will have at least as much impact as someone involved in a small environmental-focused NGO.

Regardless of everyone’s beliefs, HEC should remain a space for dialogue where all stakeholders have their place, as long as the debates are based on science, facts, and data. We don’t want to be censors by deciding who has the right to speak or not.

In your opinion, what will be the impact of the program reform on the value of a degree from HEC ?

Y.A. : In my opinion, it will strengthen it. The younger generations want to address the challenges of the contemporary world. We provide them with the knowledge and tools to do so. Companies, governments, and society in general need it.

Finally, what message would you like to convey to the HEC alumni community?

Y.A. : We need you and your advice to continue improving our education and strengthening HEC Paris’s impact on the economy and society.

Published by Thomas Lestavel