Antoine Sahler: Author, composer, performer, arranger

In the beginning, music was supposed to be something he did in the evening or on weekends, to pass the time when he wasn’t working at his real job. But, two years after leaving HEC, his hobby had become so important in the life of Antoine Sahler (H.93) that he took a leap, without a safety net, into a career as a fulltime artist.

Almost 15 years later, after several albums, hundreds of concerts and the creation of a label, we asked him if we could spend a day with him to show our readers how an author-composer-performer-HEC graduate spends his time. Strangely, he suggested we meet him in his “office”. Does a singer have an office?

10 AM: Office, Rue Lafayette, Paris

Here we are in the heart of the 9th district, very near all the business activities around the Opera. When we get there, we’re supposed to “beep” him on his cell phone, because his name doesn’t appear on the intercom. In fact, his space is so small that the management won’t allow him a spot on the directory. “With my miniscule percentage of the building, I don’t have a lot of clout, so I get by with the help of a nice neighbor,” he explains.

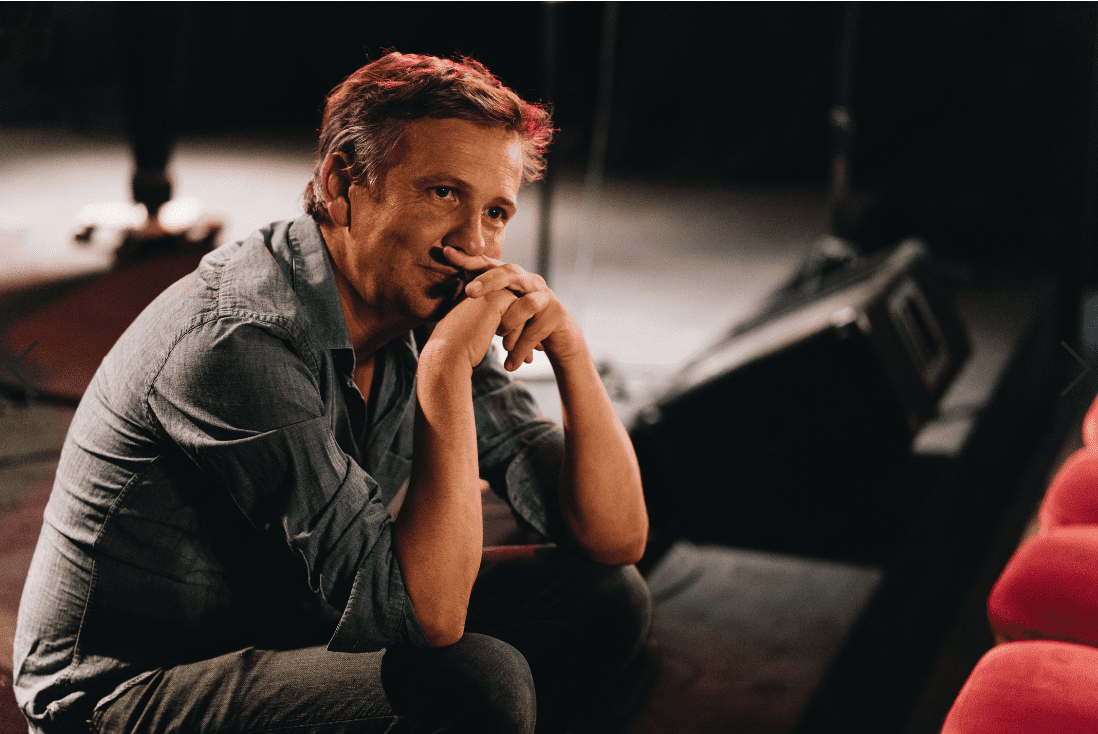

“Nice” is an adjective that comes to mind often when one meets Antoine for the first time. He has the natural warmth of a person who is truly happy with what he does, and an open smile, almost childlike. Even though he’s just about to turn 50, not without a little dread, he has gentle and youthful features and a direct, light-blue gaze. His office, a few square meters on the top floor, filled with scores and lots of different instruments, looks more like a workshop. When he isn’t touring, this is where he goes every morning to deal with whatever doesn’t relate directly to pure creation or performance.

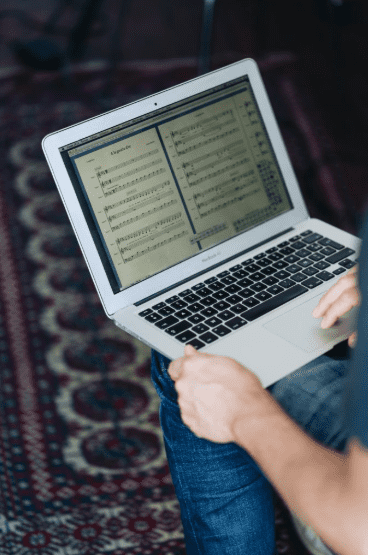

The hidden, workmanlike aspects of a musician’s life. On the wall to the left is a synthesizer that he uses to prepare “samples” of his pieces. Before a recording in a studio, each musician is given a prototype of his or her part, which Antoine creates on a piano. “This saves time in the studio, which is expensive to rent: at least 1,000 euros a day,” he explains. In the middle of the room, next to a microphone on a stand, there’s a huge brass object. It’s a tuba. “In the piece I’m working on this morning, there are a few notes played by a tuba. But, again to save a little money, I’m going to record the notes myself here instead of in the studio, because even if these notes are part of the overall harmony, they’re pretty much drowned out by all the other sounds.”

On the wall to the right, there’s the only thing in the room that fits the image of a typical office: a small table with a computer screen on top. Antoine uses this to “edit” his songs, a task that is like film editing or photo processing. “We always do several recordings for each instrument. Editing involves selecting the best parts of each one and then bringing them all together. It’s meticulous work: sometimes you cut only a single note.”

Most non-musicians are unaware that all music is created like this, in a patchwork of multiple recordings. He demonstrates with the piece he’s currently editing, a segment from an album of Breton songs that he’s preparing with François Morel. He plays the tuba part that he has just recorded. There’s one note that he doesn’t like, and he uses a simple copy-paste command to replace it with another version. “It sounds a lot better now,” he says. Since, unlike him, we don’t have perfect pitch, we take his word for it.

Jarring in the middle of this laid-back bohemian atmosphere, there’s a portrait hanging at the top of one wall of a man wearing a suit and smoking a big cigar. “That’s a naughty gift from François: a portrait of Eddie Barclay, the famous producer. He gave it to me when I created my label and he told everyone that my goal was to follow in Eddie’s footsteps.”

11 AM, Rue Cadet, Paris

Antoine spends a lot of time in his tiny office, but that’s not where he writes his songs. We follow him to the place where he usually gets his inspiration: the street. “For me, writing music shouldn’t be hard work. If I sit down at a piano, I’m stressed and I can’t come up with anything. Ideas only come to me while I’m taking a walk.” He wants his songs to have something clear and direct about them. He reveals that sometimes he finds inspiration in five minutes, sometimes six months, but it’s generally the ones that come first that are the best.

“Gainsbourg compared himself to Japanese artists who spend months gazing at a flower and then paint it quickly in a few strokes of the brush. This image fits me very well, too.” Since a song with a thesis isn’t his style, he doesn’t begin with an idea but rather with a phrase, an expression that resonates with his experience or his observations of daily life. “For example, I read in a newspaper the expression ‘dancing in the storms’ and I really liked that. It gave me an idea for a song about how we learn, little by little, to get through the tough times of our lives.”

We take advantage of a stop in a café to talk more about his creative process. “Words and music should come at the same time so that the writing isn’t too regular, too stuck into octosyllables,” he explains. “The best example of this approach is Alain Souchon, the first French songwriter to break down songwriting barriers with his really short verses and rimes hidden away in bits of text. I try to work like this in a way: Even though I love Brassens, it’s necessary to do something different.” A strong foundation in French songwriting coupled with a desire to experiment, to think outside the box, characterizes the artists he produces under his Le Furieux label. As the name suggests, the adventure he threw himself into in 2015 is not low key.

“To create a label is like being an entrepreneur, and so yes, we could say that there’s a link to the training I received at HEC. With one difference: in the music business, you can’t expect to make money. If you don’t lose much, or at least not too much, you’re doing well.” Except for the bureaucratic hurdles and the difficulties with obtaining necessary (but insufficient) financial grants, his career choice often brings him intense satisfaction.

“Sometimes I tell myself that I’m too nice, to work for free, risking some of my own money to help others. But when the label manages to produce an album, and it’s a good one, then I feel completely euphoric.” The jackpot is for a piece of music to be chosen for an ad or a film. “One of my friends miraculously had this happen recently. Just when they were about to close up shop on their label, a huge advertiser, Apple or something like that, bought the rights to one of their songs. They were able to hire three salaried employees and have funding for their work for several years.”

Business takes up very little of Antoine’s life these days, but he still has good memories of his time at HEC, and he especially appreciates his close ties to his fellow classmates. “We all took different paths, but that hasn’t affected our friendship. Of course our perspectives on certain things have been affected by the lives we’ve lived, but this doesn’t matter. We’re still happy to see each other.”

1 PM, Caverne Studio, Paris

Around lunchtime, we head to a small studio near Denfert-Rochereau where Antoine has an appointment with François Morel to continue recording Breton songs. The latter arrives right away and calls out gruffly but jovially as he comes through the door, “OK; ready to eat?”

Antoine tells me the story of how they met. “In 2005, after a concert in Toulouse, I got friendly with someone running an Harmonia Mundi music store. We got on well, we had a few drinks; it was a nice evening. The next day, out of the blue, I got a text from him: ‘The singer Juliette came into my shop and I gave her your CD!’”

“In an act of pure friendship, when she came into the store he played one of my songs, at full volume, over the speaker system, like bait. And she bit! When she got to the cash register, she asked for my name, he gave her my album, and boom! A few days later, she invited me to join a radio program that François was also participating in. He and I reassured each other, because both of us were nervous. Our friendship began that way, as two stagefright buddies.”

Watching them share Franprix salads and hearing them chat about kids going back to school, for one of them, and problems with a veranda, for the other, it’s clear that they have spent a lot of time together since they met. “At certain moments, we spend three days a week in trains and hotels, sharing the demands and intense rhythm of a tour in the provinces. So, yes, we know each other a little.” In fact, they know each other so well that Antoine’s name is now closely associated with that of his actor pal.

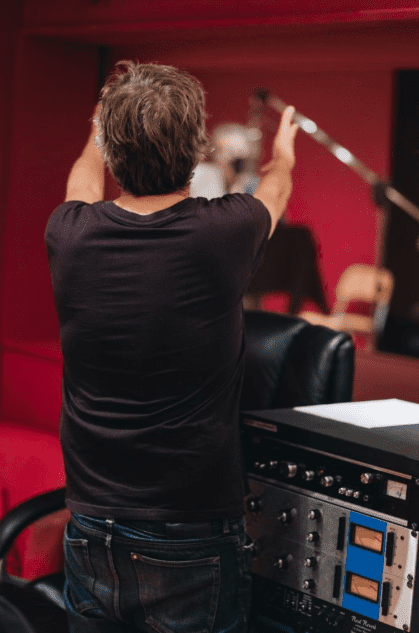

“On the one hand, it’s really lucky for me, because it gives me access to people who count in the show business world. On the other hand, I’ve become so identified as ‘François’s musician’ that it’s hard to interest them in my other projects.” When Antoine and François leave the little dining room to enter the studio, it becomes very clear just how well they complement each other. In this absolutely silent space filled with machines that can measure and adjust the tiniest detail of any possible sound, Antoine is obviously in his element.

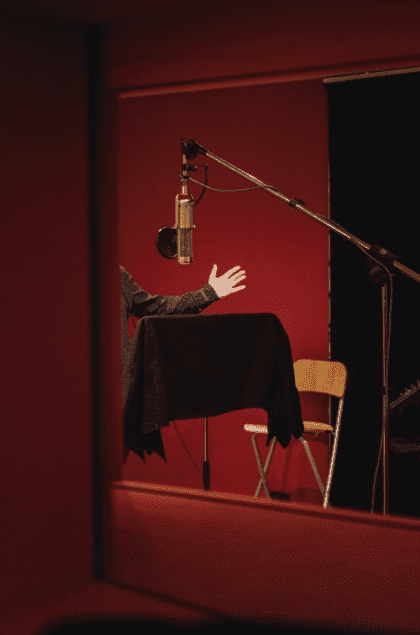

François Morel, alone in his recording cubicle, acts like he is in front of an audience. While one of them gestures, yells and frowns, the other one concentrates on pinpointing the right sound, watches out for wrong notes, suggests alternate intonations. The song they’re recording lends itself well to this: it’s a long Breton ballad without beginning or end, telling tales of crazy village gossip and shady family stories straight from the Morbihan. François Morel conveys all of it in an irresistible mock-heroic tone. Sometimes he makes a mistake with the rhythm and stops. If the rest of the song is good, they “drop” (start recording again after the last good measure). Sometimes they just do a “patch” (a really short recording to correct a small sound error, one note.)

But Antoine is not trying to achieve perfection. “There’s a very popular software program that automatically corrects any voice glitches,” he explains, “but most of the time I don’t use it. I like having a few imperfections. We shouldn’t try to smooth everything out.”

7 PM, Forum Léo Ferré, Ivry-sur-Seine

Tonight, Antoine is giving a concert in Ivry-sur-Seine. The concert hall is called Forum Léo Ferré. A grandiose name for a tiny restaurant with a stage and three rows of seats. Partly an informal theatre venue, partly a neighborhood restaurant hangout, with a portrait of Zapata on the wall and thrift-shop furniture, this place is run by people who are passionate about the arts.

“Small venues are rare,” Antoine says with regret. “But they’re essential to keeping French songwriting alive.” Such places give artists the chance to test new ideas in front of a live audience. “Tonight, I’m going to try combining songs with reading short stories, and I’ll play two songs that haven’t been performed before.” These small concert halls attract dedicated fans and sometimes journalists and people looking for talent for larger performance spaces. “To promote an album, we can do one or two concerts in a big hall, with a little advertising and some invitations, but it’s really expensive. In Paris, even if you sell every ticket, you still lose money, unless you charge prohibitively high prices.”

Before the concert, there’s the soundcheck, which involves balancing the levels of the voices and instruments. Tonight this job is a bit complicated because Antoine has invited Donia, one of the artists on his label, to sing with him. They have to position the microphone in the right place, adjust the monitoring (the sound played on the stage so that the artists can hear it), the height of the piano bench, etc. All that has to be done with, in the background, screaming children playing in the courtyard, kitchen noises, and the odor of the white vinegar being used to wipe tables. After sharing a plate of cold cuts for dinner, the two artists retire to their miniscule green room. At 8:30 PM, the restaurant’s customers move toward the stage, the lights are dimmed, and Antoine appears.

“Hello Ivry-sur-Seine!” he calls out, joking about the 20 or so people in the audience. He then launches into a program that is basically songs from his latest album. In his clear, slightly frail voice, he sings, in a gently nostalgic mood, about such themes as love late in life, an obsession with lists, an aversion to marriage, the difficulties of joint custody of children… Alternating mischievous jokes and sentimental refrains, playing the piano with ease, he fills the room with an intimate, tender charm, reminiscent of Vincent Delerm or Albin de la Simone. Judging by the two encores and the applause he receives, the public is thrilled, and so is he.

“I really enjoyed that, even if I slipped up once or twice. On the stage or in the studio, I tell myself how lucky I am to be able to do something that I love.” It’s clear now that he isn’t questioning his future. “In my field, trying to anticipate what will come next is the best way to make yourself miserable. Artists who count their chickens before they’re hatched will only frustrate themselves. So, for me, my goal is just to keep going on.”

Also see “24 Hours with Hedwige Chevrillon backstage at the BFM”

Published by Arthur Haimovici