24 Hours with Jean Lalo (H.85)

Devoting his retirement to helping others: that’s what Jean Lalo (H.85) has chosen to do. A Red Cross volunteer, he decided to create community vegetable gardens for isolated senior citizens. A chat with this HEC alum who has a big heart and a green thumb.

In our masked post-lockdown world, some believe it’s hard to recognize people. But, here on tiny Rue Berthier in the heart of Versailles, Jean Lalo (H.85), a 63-year-old retiree, is easily identifiable in spite of the protective glasses that hide his eyes. Now that shaking hands is forbidden, he offers a friendly “hello” in a way that shows he wishes he could be more demonstrative. “Welcome to our little local hangout. You’ll see; it doesn’t look like anything special, but we feel at home here!”

9 AM, local center on Rue Berthier

The center, a bequest from a generous donor, is a small private residence with terra cotta tiles on the ground floor. It has rooms in all sizes; the largest are used for meetings, meals or just relaxing, while the smaller ones serve to store tools, clothing or non-perishable food items. The windows give views of the surrounding garden. The Red Cross has a dozen facilities like this in the Yvelines district and thousands all over France. They are used for distributing clothing and food to people in need, or for training sessions and other purposes. “There’s always something going on here,” Jean says happily. “We even organize activities on Saturdays for people who have Alzheimer’s.” Today, the place is really empty thanks to the coronavirus, which has stalled comings and goings for the past two months. This morning, two people have gotten up early to work with Jean: Valentin, 28 years old, and Carla, a 24-year-old young intern. The retiree welcomes their help; he admits he’s “a bit worn out”.

As a volunteer ambulance-driver, Jean hasn’t had much time to relax, between responding to emergency calls and taking people who might have contracted the coronavirus to the hospital. “In these cases, if we’re late, someone’s life may be at risk,” he explains. This experience has made him extremely careful about protective measures. He constantly reminds his colleagues to adjust their masks. “I’m a stickler for the rules about staying safe. Seeing someone near death is hard to take.” This Wednesday morning in May marks a transition for Jean: it’s the end of his involvement in emergency services and his return to an initiative he created that’s particularly close to his heart: Les Rencontres aux Pot’âgés (Community Gardening for Seniors). As the name suggests, isolated seniors can meet others through taking care of a shared vegetable garden. Benefiting from a Red Cross innovation-support program, the project should have been launched at the beginning of the year. The pandemic spoiled that plan. “For people who are already suffering from being too cut off from the world, the lockdown could be a real disaster,” he worries. “Now there’s even more reason to get this effort up and running.”

Today, then, will be devoted to getting ready for a brighter tomorrow. Do-it-yourself jobs and meetings are on the menu. A ray of sunshine begins to warm up the center on this chilly morning, and we hear two new voices at the entrance: Florence and Anne, Jean’s wife and sister-in-law respectively, have come to help out. “Here are the only two old people you’re going to see today,” Jean jokes. Then, perhaps because he feels a little guilty about his comment, he adds, “Anne is going to share her expertise as a landscape architect as we begin to set up the first vegetable beds on the property.”

10AM, hardware store and the regional office

While some mow the grass, others unpack tools. Very quickly a technical issue threatens to bring everything to a standstill: the Philips-head screwdriver is missing. Valentin is sure he put it back in its place. After a fruitless search, Jean decides to stop off at a hardware store on his way to the regional Red Cross office, and he hops into the truck. Valentin is driving, and Jean teases him about the jerky start. “It’s the first time I’ve driven this truck and the gears are a bit stiff,” the young man laughs. It’s just two days after the end of the lockdown, and the people we see in the streets apparently haven’t yet grasped the concepts of social distancing and correct mask-wearing. “Look at that guy, with his nose sticking out! That doesn’t do any good at all, mister!”, Jean cries. Inside the hardware store, here we go again. Two customers have actually removed their masks and are having a conversation just inches from each other. Jean doesn’t hold back; he tells them, rather firmly, to put their masks back on. His uniform seems to impress them, because both the non-maskers quickly do what he says. Back in the truck, Jean is fuming and Valentin, though silent as he concentrates on shifting gears, seems to share his feelings. What they’ve witnessed over the last few weeks hasn’t made them optimistic. “The hospitals we’ve been to over the past few days are pretty worried about what’s going to happen now that the lockdown has been lifted,” Jean explains. “If it goes on like this, I’m afraid that 10 days from now, we’ll be in trouble again.”

The regional office of the French Red Cross looks just like what one would expect of a non-profit. The rooms are painted orange and the air is steeped with the smell of stale coffee. Plates are stacked in a sink and there’s a box of sugar nearby. And of course everything is bathed in bright white fluorescent light. At least it’s not flickering. Several people are sitting in front of laptops. Ever since the beginning of the pandemic, this office has been the headquarters of a regional service, a special covid 19 crisis unit. “Get ready to be ready,” is the guiding principle. After saying hello to everyone, Valentin and Jean head to the back of the building, where new kits for raised vegetable beds have been stored. Along with things that look like models of roundabouts with metal edges, there’s a jumble of platforms set up like shelves, very practical for seniors who might have trouble bending over. All the kits are, of course, ecological, designed to conserve water, and… in pieces, needing to be put together. “I’ve always been excited by gardens,” Jean says. “I remember once watching the show ‘Quiet: Something’s Growing’, and the host, Stéphane Marie, had fixed up an old lady’s vegetable garden. When she saw what he had done, she told him that he had given her a new lease on life. That really had an impact on me and that’s what inspired me to create Rencontres aux Pot’âgés. And since I was a Red Cross volunteer, I found out that they were looking for projects. The stars were aligned.” As he explains the origins of his initiative, Jean loads the kits into the truck, careful to leave one behind for the regional office.

11 AM, back to the garden

Back to the local center, where everything smells like freshly mown grass. The raised-bed kits are unloaded from the truck and placed around the lawn in an arrangement Anne, the landscape architect, has carefully planned. We set the bases of the structures into the ground and then get them ready for the soil, which volunteers are supposed to go pick up this afternoon. Jean takes advantage of the downtime to get his phone out of his pocket and connect to the Red Cross volunteers’ Facebook page. It’s filled with challenges started up during the lockdown. “I even did 10 pushups for one of these things. Not bad for a guy my age to pump myself up and down like that, huh?”, Jean laughs. Under the video of his feat, someone has posted a picture of four pairs of shoes, with the comment, “I’m giving you eight more pumps.” Facebook humor is certainly alive and well. “I love exchanges like this!” he says. Then, he looks around and cries out that he will go pick up some pizzas for lunch. Everyone approves, which shows that hungry stomachs have ears.

11:30, heading to the pizzeria

As we drive to the pizza place, we pass an array of elegant homes. “We’re lucky to be based in one of the nicest neighborhoods of Versailles,” the volunteer explains. “We’re sort of the aristocrats of the French Red Cross! A big plus is that some of the local residents have offered to let us set up our vegetable gardens on their properties. This pandemic has inspired a lot of solidarity just about everywhere. We’ve seen people helping out neighbors they had never even met before.” In the same spirit, the Red Cross reports an increase in volunteers. “This is good news, because if this project takes off and is extended all over France, we will need around 5,000 more volunteers over the next three years,” Jean explains. When we get back to the center, we greet some new arrivals, including the vice president.

12 noon, the dining room

Sophie Lehuard is one of Rencontres aux Pot’âgés’ earliest supporters. She’s the one who presented the project to the regional office. “In addition to creating new relationships, the goal is to give isolated seniors a purpose in life. When you have a goal, you can move forward,” she says. The lunch is an opportunity to talk about another aspect of the project: its gastronomic appeal. “The lockdown encouraged people to rely on themselves and to eat healthful products. A vegetable garden is the ideal complement to this,” Jean points out. Before the pandemic, he contacted Jean-Baptiste Lavergne Morazzani, multi-starred chef of the gourmet restaurant La Table du 11 in Versailles. The chef knows a lot about vegetable gardens (his own covers some 1,500 square meters), and he has closely followed Jean’s project, even offering to create an exclusive recipe for the Rencontres to help motivate participants. “This solidarity is just fantastic. We are going to be able to set up a real network,” Jean enthuses. Someone brings a bowl of strawberries to the table, a reminder of the work that needs to be done. After dessert, Jean takes a break outside for a few minutes and then heads to the upstairs conference room.

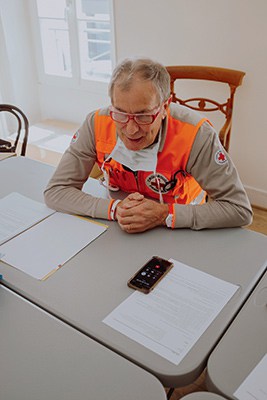

2 PM, telephone meeting

A portrait of Henry Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, hangs on the wall at the back of the room. Under his bearded face are listed the values of the organization: “Humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, volunteerism, unity and universality.” Jean puts his telephone on the big table and turns on the speaker. At the other end of the line is Mélina Ferlicot, head of the Versailles Community Center for Social Action. She is going to provide a list of the most socially isolated seniors in the area. She says she believes they should wait to launch the project until September, once the crisis is more under control. A bit disappointed, though not surprised, Jean agrees with this prudent decision. “That makes sense. We’ll make as much progress as possible, so that we’ll be ready on day one,” he says, although it’s clear he’s a bit impatient.

The Rencontres project was born out of a social conscience Jean developed over many years. “I remember a business dinner at the beginning of the 2000s,” he recalls. “I was sitting next to Sir Bob Reid, who had been an executive with Shell United Kingdom. We were talking about the Brent Bravo oil-rig disaster in the North Sea that had cost the lives of two people in 2003. Suddenly Reid put down his fork, looked me in the eye and said, ‘You know, Jean, we have really screwed up.’ It was like a bolt of lightning. I told myself that I didn’t want to be part of that world anymore. From that time on, I always encouraged the companies where I worked to support social and environmental causes. It was a top priority for me.” He then picks up a big bottle of hand sanitizer. “This bottle was produced by my former employer. His business is marking highways, but he converted one of his production lines into manufacturing hand sanitizer. He sent me bottles of it as a kind of gesture. Even when your beliefs seem unjustified or a little crazy, you have to be true to them and never give up.” He then explains how he won some lawsuits against big polluters and trained the emergency-service teams he has been working with.

Jean, in other words, has been a kind of whistleblower even before the term was invented. “To get involved with the Red Cross was a logical step for me. I was educated by Jesuits. I learned to serve, and therefore I serve.” He has been head of innovation and of research and development, a consultant, an auditor whose investigation led to a company’s shutdown…all sorts of impressive titles that have nothing to do with his life today. “I don’t have any regrets,” he insists. “I’m aware that I graduated from a school that helps create a world I no longer want to have anything to do with. But my experience has given me the necessary perspective to criticize that world, and perhaps to change it.”

4 PM, city hall

Grabbing the keys to the truck, Jean leaves the building. He heads to Versailles’ city hall for his last meeting of the day. He and Sophie Lehuard are scheduled to meet with Sylvie Piganeau, the assistant mayor whose job is to work with local non-profits. What’s at stake: getting the city’s support. The assistant mayor’s office is decorated with stacks of multi-colored files and a discrete photo of the Pope, smiling, with a dove perched on his finger. It’s a bit difficult to break the ice, since everyone is wearing masks. They chat about municipal employees and elected officials whom Jean has already met. Then there’s a lot of name-dropping that the newcomer can’t follow. Finally Jean, who has been sitting with his hands modestly immobile until then, begins to make big gestures as he describes his project enthusiastically. “You’re preaching to the choir,” the assistant mayor tells him. In fact, she says, the mayor has even suggested offering the services of the city’s own eco-gardeners to support the initiative. She also promises to loan him some municipal composting containers. As he leaves city hall, Jean remarks, “You know, I really do like this city.”

A non-profit project can’t be accomplished without support. Maintaining good relations with local and municipal authorities is essential.

5 PM, the future

Back to the local center on Rue Berthier, where the first vegetable beds have already been set up. Valentin, Carla, Anne and Florence fill them with dirt. In some of the beds they use a “lasagne” technique: multiple layers of natural materials that will compost to nourish the plants. It’s an approach borrowed from permaculture. There are still a few strawberries left in a bowl. At the window of a nearby house, an older man watches with interest as the vegetable garden takes shape. Maybe he’ll be one of its gardeners someday.

Thomas Chatriot

Published by Flavia Sanches