Romain Troublé and the Tara Polar Station: A UFO at the North Pole

Led by Romain Troublé (M.01), the Tara Ocean Foundation, renowned for its schooner, is currently embarking on a colossal project: an international polar station dedicated to Arctic exploration, which will be christened in early 2025. HEC Stories got on board.

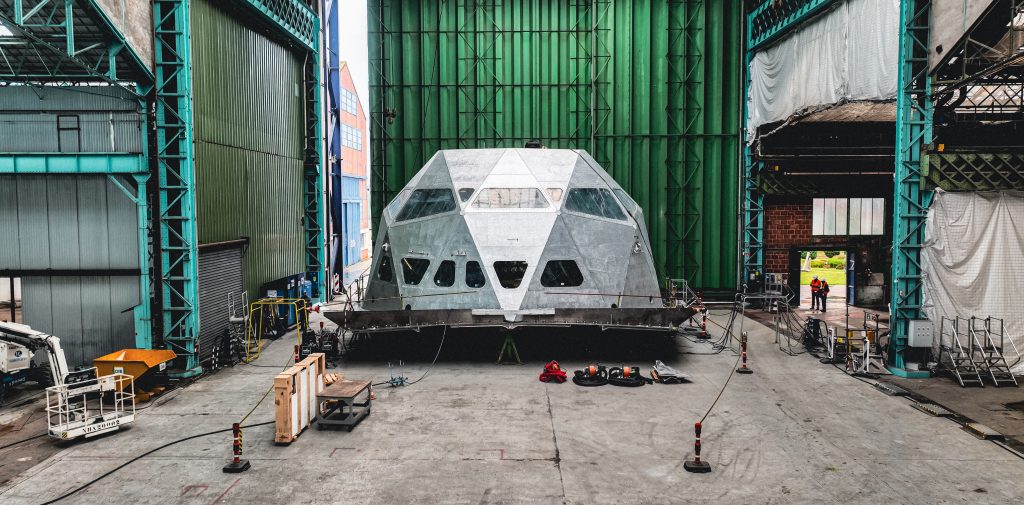

A circular aluminum vessel, 11 meters tall and 26 meters long, currently stands at the heart of the construction site of Constructions Mécaniques de Normandie (CMN). Covered in scaffolding, the craft has just received its centerpiece: a 30-ton geodesic dome, giving it the appearance of a flying saucer. This isn’t about exploring space, but the Arctic. The Tara Polar Station – TPS for those in the know – is a novel project of the Tara Ocean Foundation. An international initiative, it will soon be captured and drift with the ice with the purpose of observing the melting of the ice pack and how the ecosystem adapts to climate change and pollution during long scientific expeditions.

Romain Troublé (M.01), executive director of the NGO and an explorer himself, eagerly guides his investors through the heart of the project, slaloming between the workers – around forty in total – who are diligently welding and insulating the station, mostly made of aluminum panels. Such a vessel has never been built before: the station is a gigantic prototype. The heat of late August inside the shipyard’s glass roof is sweltering, even more so inside the station as insulation is installed. Alongside project director at CMN Ludovic Marie, Romain is pleased. The construction is only slightly behind schedule, a rare achievement for such a complex undertaking. “We’re working with adventurers,” explains Ludovic Marie. “And it shows. It’s rare to have a team where everyone contributes to something for the greater good.”

Such a vessel has never been built before: the station is a gigantic prototype. The origin of this venture lies in a family’s love for the ocean and discovery. Agnès Troublé, known as Agnès b., and her son Étienne Bourgois, Romain’s cousin, created the Tara Foundation in 2003, transforming the schooner Antarctica into a floating scientific laboratory. Their boat traveled 400,000 kilometers, visited 60 countries, and raised awareness among thousands of citizens about ocean conservation. In 2006, trapped in the ice pack, schooner Tara drifted across the Arctic Ocean during an 18-month expedition: the direct inspiration for the Tara Polar Station project. “This ship was designed based on the schooner’s plans,” says Romain. “It’s round, with no keel, to escape the pressure of ice sheets and allow it to rise.”

The TPS will be launched in early October, with a grand christening ceremony planned for early 2025. The vessel will then head to Lorient for initial trials, followed by testing in Narsarsuaq, Greenland, before drifting off the northeastern coast of Russia. Led by the CNRS, Laval University in Quebec, and the University of Maine in the United States, the scientific mission will be developed by around forty laboratories spread across twelve countries. “It’s a technical, human, and scientific feat,” says Romain.

At the Tara Polar Station construction site at the CMN facility in Cherbourg, a few weeks after the installation of the geodesic dome, August 2024. ©Estel Plagué

Eight Months Trapped in Ice

Although, for now, the interior is filled with cables and pipes, the first two floors of the station will eventually house offices, laboratories, a kitchen, and even a banya (a traditional Russian sauna). A temperature of 11°C must be maintained inside, while the outside temperature can drop to as low as –52°C. Another significant challenge is to make the station as environmentally friendly as possible. It will rely on wind and solar energy to power its equipment, and hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) will be used for propulsion.

The hull of the Tara Polar Station before the assembly of the final C200 block ©François Dourlen-Tara Ocean Foundation

The hull of the Tara Polar Station before the assembly of the final C200 block ©François Dourlen-Tara Ocean Foundation

“We were just discussing the color of the fabric for the crew’s rooms,” jokes Pierre Mienville, in charge of partnerships. For the future crew, who will remain confined within the station for several months, the finishing details are far from trivial. The structure, which must be self-sufficient for 500 days, is designed to accommodate about twenty international explorers in the summer and twelve in the winter: scientists, sailors, doctors, or artists, whose selection will begin next year. Priority will be given to those who have already sailed aboard the Tara schooner. They must prepare to spend up to eight months in the station’s 400 square meters of living space, under extreme conditions: six months of night and six months of day in the Arctic. The scientists will take samples by diving into the water via the moon pool, a tubular airlock located in the center of the station. They won’t even be able to use headlamps, as artificial light scares away the ecosystems. These drifting missions, named TaraPolaris, are expected to happen ten times—at least, that’s the plan.

Being stuck without knowing the exact end date of the expedition poses a psychological challenge, one that Romain Troublé has “experienced firsthand.” The explorer knows the Arctic pretty well. Enthusiastic about studying living organisms from an early age, Romain once wanted to become a veterinarian. He eventually graduated with a degree in molecular biology. In 2000, after returning from the America’s Cup, where he competed as a sailor, he decided to pursue project management by enrolling in HEC. It was also the beginning of the internet era. After obtaining a master’s degree in “Net Business” in 2001, Romain took charge of the digital strategy for Cerpolex, a company specializing in polar expeditions, including trips to northern Siberia to “excavate mammoth carcasses.” He spent three years traversing the poles before embarking on two polar missions aboard the Tara schooner in 2006 and 2013.

Romain Troublé (M.01) visiting the Tara Polar Station construction site at the CMN facility in Cherbourg, August 2024.

Romain Troublé (M.01) visiting the Tara Polar Station construction site at the CMN facility in Cherbourg, August 2024.

The sea and science have always been familiar territory for him. A recognized skipper, his father, Bruno, competed in two Olympic sailing events—Mexico in 1968 and Montreal in 1976—before founding the Louis Vuitton Cup, the selection races for the prestigious America’s Cup. “Throughout my childhood, I would join him at boat races,” recalls Romain. “I must have been a nuisance, but I was there, waiting for him to return.” He also remembers his grandfather’s boat in Antibes, which was already named Tara, after the plantation of disillusioned heroine Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind.

Joining the Tara project was a natural fit for him. “I was a sailor and had spent five years studying science. I had spent a lot of time in Siberia and the poles,” he says. “When my cousin and my aunt, Agnès b., decided to acquire the Tara project, I was one of the first on board. Tara combines business, politics, and science. I speak the same language, I know all the terms.”

A €21 Million Mission

The French government, which had announced a one-billion-euro investment for polar regions as part of the France 2030 plan, has just injected €13 million into the project, whose total cost is approximately €21 million. The Tara Ocean Foundation, which already counts BNP, Capgemini, Veolia, and the Albert of Monaco Foundation among its partners, is still facing “a major fundraising challenge,” seeking an additional €2 million in funding.

The 30-ton geodesic dome of the Tara Polar Station, installed this summer on the hull of the vessel. ©François Dourlen/Tara Foundation

Between European scientific summits and hosting public figures on the construction site, Romain devotes much of his time to lobbying. He doesn’t hesitate to share content on LinkedIn that criticizes ecologically harmful practices, highlighting the importance of “employer branding” for donor companies. “This project is a great example of action. Companies can build long-term credibility by supporting initiatives focused on planetary biodiversity. We are not in the habit of criticizing just anyone. Our work is centered on research, so we stay pragmatic, fact-based, and not at all dogmatic.”

The most pressing issue, of course, is the urgency of the situation. “We often talk about climate at the expense of biodiversity. But biodiversity is incredibly important; our lives depend on it. Our main hope is to contribute to the protection of the Arctic and to predict what will happen in the future. We are dealing with an extreme ecosystem, and all extreme ecosystems on the planet are teeming with molecules that we don’t yet know.” He then delivers a chilling truth that alone motivates the massive undertaking of the Tara Polar Station: “In twenty years, each summer, the ice will completely melt. Current PhD students tell us they are the last generation who will be able to study it. So, we have to go now.”

Published by Estel Plagué