Jalil Benabbés-Taarji (H.83): the man behind AKAN Collection

Born in Fez, raised in Marrakech, educated at HEC, shaped by New York and a banking career in Paris, Jalil Benabbés-Taarji took time before returning to Marrakech. There, he reconnected with the hospitality company co-founded by his father, the Tikida Group, and became one of the key contributors to the city’s tourism boom. Today, with AKAN, a collection of three “Houses” — Les Deux Tours, La Villa des Orangers and El Fenn — he is writing another story: that of discreet luxury, deeply rooted in Morocco, where architecture, memory of place and care for teams matter just as much as guests.

From Fez to Marrakech: a child of the French education

“I was born in Fez, but in reality, we’ve been Marrakchis for five generations,” smiles Jalil Benabbés-Taarji. His childhood unfolded to the rhythm of family moves, between Marrakech, Rabat, Agadir, then back to Marrakech during adolescence. Everywhere, the same backbone: the French school system.

“I’m a product of the French mission,” he sums up. With a Bac C diploma in hand in 1978, in an educational system where career guidance was still fairly rudimentary, he had little sense of where to project himself. The name HEC would appear… by chance, one evening.

The HEC spark… and the Lakanal trial

A dinner at friends’ house, a young man at the center of attention announcing his admission to HEC. “I was impressed by his personality, the way he spoke. The name of the school stuck somewhere in my mind. When the time came to choose, those three letters came back,” recalls Jalil, who remembers it as if it were yesterday.

With little real knowledge of academic tracks, he chose the HEC preparatory route at Lycée Lakanal. He was just seventeen and a half when he left Marrakech for Sceaux, discovering boarding school, the cold of the Paris region, “by-the-book” hazing, and the brutality of a comment that would stay with him.

“At the end of the year, my French teacher wrote: ‘Should consider changing tracks.’ It felt like a slap. I still talk about it today.” Wound or fuel? “It lit a fire in me. I wanted to prove him wrong!” The times were tough: one-year prep classes, unforgiving statistics, most admitted students being ‘squared’ in their second year. Jalil was one of them, became Z of his class — class leader, and therefore head of hazing — and held on.

Jouy-en-Josas: discovering a new world

In 1980, he was finally admitted at HEC Paris. And there, a change of scenery:

“Jouy holds only good memories. A magnificent campus, sports facilities, top-level professors.” He played tennis, joined HEC’s swimming team for triangular tournaments with École Polytechnique and Centrale — “we were often last, but we were there” — and discovered a gentler life than the Lakanal boarding school. To celebrate his admission, his father gave him a small Volkswagen Golf, allowing frequent trips to Paris to see friends… and his “girlfriend.”

Yet another episode left a mark, as powerful as his prep teacher’s remark. At just nineteen, he was summoned by the school’s director. “He wanted to see what a young Moroccan looked like, how I spoke. At one point, very kindly, he asked: ‘Are you doing HEC to go into politics? Because it’s difficult to do politics in Morocco.’ That question stayed with me all my life. It pushed me to take an interest in politics, but also to remain clear-eyed about its limits.”

A “semi-sabbatical” year and New York on the horizon

Upon graduating from HEC in 1983, Jalil felt too young to jump straight into working life. He allowed himself a pause he describes as “semi-sabbatical”: a postgraduate degree in international taxation at the Sorbonne, and the rest of the time spent in the dark cinemas of the Latin Quarter. “I was a film buff. I kept a log of every movie I watched. Taxi Driver, The Seven Samuraïs… some I saw seven times.”

Then came banking. A first three-month internship at Crédit Lyonnais in Paris, followed by a decisive opportunity: a long internship in New York, at 95 Wall Street. He eventually stayed there for eighteen months.“New York in the mid-80s was electric. I had friends there, an intense life.”

Back in Paris, he joined Crédit Lyonnais’ treasury department and settled near Canal Saint-Martin. “Metro, work, sleep. After two years, I told myself I couldn’t go on like this.” An appendicitis crisis accelerated the turning point: operated on the very evening of his farewell party, he returned to Morocco on July 1, 1988, literally “on a chair,” as he likes to recount. Exactly ten years between Paris and New York.

The missed textile venture, then a return to Marrakech

Back in Morocco, Jalil did not immediately join the family business. He worked on an industrial textile joint venture project, in a country where the sector was booming. Through a banker friend of his father, he became associated with a major French industrialist, manufacturer and owner of the Fusalp brand, now iconic once again. Two projects followed — socks and ski apparel — but the premature death of the French executive, followed by the first Gulf War, derailed everything.

“There was a combination of circumstances. The company no longer wanted to hear about Morocco. Everything collapsed.”

After countless trips between Casablanca and Marrakech, the question became unavoidable: why not join the family business? In 1990, he finally joined the Tikida Group, founded in 1973 by his father and their long-time partner, Guy Marrache.

“My father wanted me to find my own path. I had never planned to join the family business. And then it became natural.”

Tikida, a pioneer of Moroccan hospitality

At the time, the Tikida Group was building and owning its first major hotel: The Tikida Garden in Marrakech, 200 rooms, one of the first of its kind, in the Palmeraie.

“Until the early 1990s, almost all of Marrakech’s hotels were in urban areas. The Palmeraie was almost the end of the world,” recalls this pioneer.

The name Tikida comes from the Berber word for the carob tree, in homage to a majestic tree that once stood at the heart of the property, by the pool. From this first hotel, the group expanded in Marrakech and Agadir, notably through partnerships with major international operators. Tikida became one of the pioneers of all-inclusive resorts in Agadir in the early 2000s.

Over a few decades, the group — owned by two families — became a major player: around ten hotels, nearly 3,000 rooms and as many employees. By agreement with their historical partner, the Benabbés-Taarji family undertook an unexpected and opportunistic diversification. Three years ago, what Jalil calls “an alignment of the stars” occurred.

AKAN: one foundation, three Houses, one vision

In 2022, an email changed the trajectory. It came from Gwenaël Bourbon, a French broker met briefly in 2020, two weeks before the pandemic. At the time, Jalil had declined his proposals: interesting hotels, but too close to the Tikida model. Two years later, in the same email thread, another property appeared: La Villa des Orangers. “There, it took me three minutes to reply — just enough time to validate with the head of the family. There was a real love at first sight, even before looking at the numbers.”

Les Deux Tours followed, and last November, El Fenn. Three very different Houses, but one shared DNA: exceptional places steeped in history, created by families, already loved by their guests — places that Jalil and his teams do not wish to transform, but to extend. To unite them, a name was needed: AKAN. “AKAN, in Berber, means foundation, structure. AKAN is the guardian: it protects the identity of a place and reveals its beauty.” AKAN thus became the first 100% Moroccan-owned boutique hotel collection, with over 300 employees and, for now, three “Houses,” as Jalil likes to call them.

“We are not about ostentation, but elegance and refinement. A simple, discreet luxury, where people are at the heart of everything — for our guests as well as our teams.” A dedicated guest-experience department, led by Wafa Laksiri, ensures this constant attention. Behind the scenes, another level of commitment unfolds: heavy renovations of back-of-house areas, staff facilities, boiler rooms, energy savings (biomass from olive pits, heat pumps, photovoltaic systems whenever possible).

“We are long-term owners, not asset flippers. We invest for the long run, in what can be seen… and just as much in what cannot.”

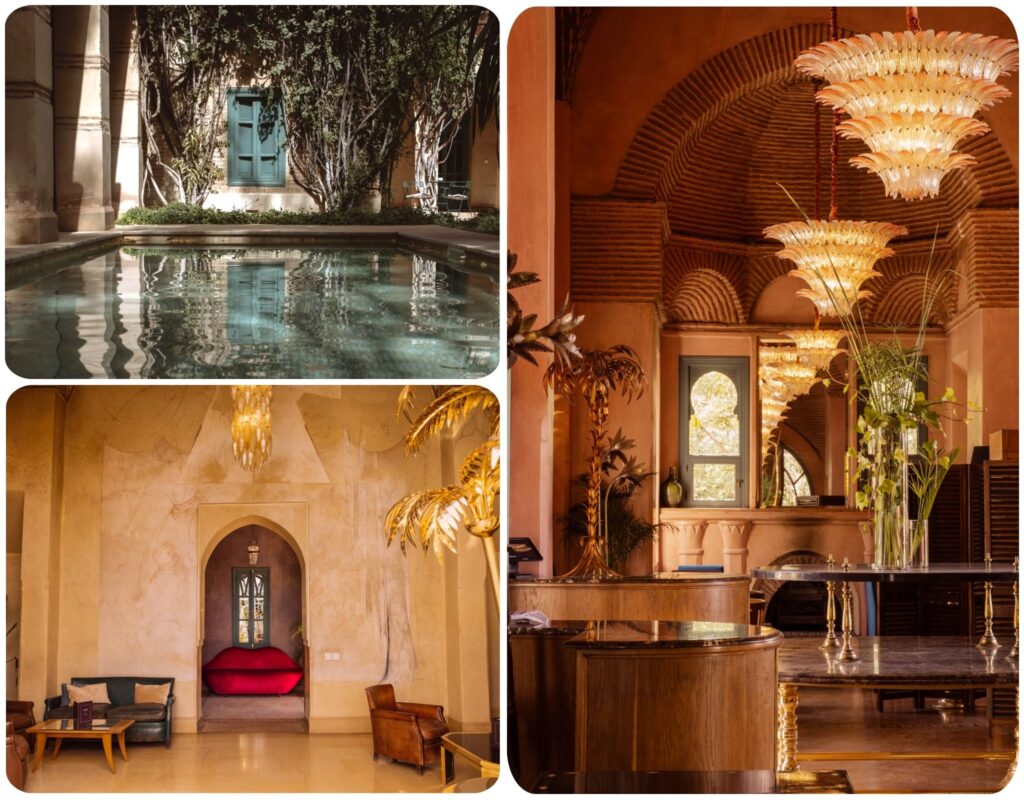

La Villa des Orangers: a secret riad at the gates of the Medina

La Villa des Orangers, under the direction of maître de maison Souheïl Hmittou, hides just minutes from the Koutoubia. Built in the 1930s for a Moroccan judge and transformed into a luxury riad in 1999 by Pascal and Véronique Behérec, it is today the oldest Relais & Châteaux property in Africa and the Middle East— a label that attracts and reassures the many American guests staying there for their first time in Marrakech.

“It’s a 1930s house that became an assembly of three riads, three patios,” explains Jalil. “We preserved the original frescoes, and in one corridor we even show all the stages of their creation, like an open-air workshop.” The house features 33 rooms and suites. In the restaurant, the chef respects tradition, sources locally, and ensures fish follows responsible fishing principles. Guests wander between pools, orange trees, hushed lounges and discreet terraces overlooking the UNESCO-listed Koutoubia.

La Villa des Orangers was also AKAN’s gateway. “When Gwenaël’s email arrived, I called my father. We felt it was time to diversify, to move beyond Tikida’s large resorts. La Villa des Orangers ticked every box: history, stone, service, human scale.”

Since the acquisition, the house has closed twice for major renovations — almost invisible to guests. Plumbing, electricity, bathrooms, air-conditioning: “Everything you don’t see,” he sums up, “but that ensures the house remains beautiful for a long time — beautiful from the inside out.” Its reputation and consistency earned it a Michelin Key in 2025.

Les Deux Tours: a garden designed by Charles Boccara

The first House to visit, Les Deux Tours, lies in the Palmeraie. A three-hectare estate originally designed as a set of six villas by architect Charles Boccara, “a major figure of Marrakech urbanism, whom I had the pleasure of knowing more than thirty years ago. Boccara has a true signature — a ‘Boccara art’ found throughout an entire district of Marrakech. At Les Deux Tours, you feel it everywhere,” explains Jalil.

Indian doors, soaring ceilings — “luxury lies in wasted space,” sums up director Mohamed Hejjaj — marble blended with Moroccan craftsmanship, and immense Murano glass chandeliers in the restaurant. The grounds include a 7,500 m² vegetable garden, goats providing milk, a pair of peacocks, lemon trees, olive trees, even a hybrid tree — grapefruit crossed with navel orange. At the far end, a long heated swimming pool cuts through the greenery.

Underground, six biomass boilers run… on olive pits — another way of anchoring the house to its land. Les Deux Tours attracts a largely European, often francophone clientele, already familiar with Marrakech, coming for “the garden, the sun, the pool,” sometimes venturing into the medina only once or twice during their stay. It is the Palmeraie house, the city’s “garden” angle.

El Fenn: the Medina as a living work of art

AKAN’s most recent acquisition, El Fenn — “art” in Arabic — is undoubtedly the most iconic. Conceived and founded by Vanessa Branson, it is an interweaving of thirteen riads in the heart of the medina. One enters through a large wooden door, anonymous in a narrow alley, giving nothing away of the scale inside.

Inside, you get lost — and that is the point. The Pink Courtyard, acquired in 2004, was originally just a pool surrounded by three rooms, a kind of Moroccan feng shui. In 2007, the Orange Courtyard was added, centered around an improbable tree — a fusion of orange and lemon, grown for orange blossom. A spa followed, new rooms, and a spectacular rooftop with an uninterrupted view of the Koutoubia, housing both restaurant and kitchen.

Today, El Fenn has 41 rooms and suites… without keys. In some suites, the floors are made of camel skin — extremely difficult to maintain, but creating a unique dark leather patina. At the entrance, an installation of babouches resembles a contemporary art museum — especially since a pair of Converse sneakers, belonging to Vanessa Branson’s former partner, slipped in upside down. An anecdote that resonates with her friends and the initiated. On the rooftops, among sunset dining terraces, tortoises live — brought upstairs every winter morning to enjoy the warmth. Three cats rule the patios, including Isra, who left a neighboring home for good to settle here.

In the kitchen, El Fenn claims a distinctly Marrakchi identity, with lamb tanjia, alongside bold vegetarian creativity: almond falafels with lemon and rosemary, vegetarian tagines, Moroccan sweets — all sourced within a 50-kilometer radius. From the rooftop, the view of the Koutoubia — “our Eiffel Tower,” as Amine Belkhayat Zoukari, the new director returning from Asia, puts it — reminds visitors they are at the heart of a city that has become one of the world’s iconic destinations.

El Fenn has hosted film shoots and very private celebrations, including Madonna’s birthday, but Jalil insists: “Our goal is not to change El Fenn. We pay tribute to those who created it. We are caretakers, not inventors. It’s our responsibility to preserve the soul of the place, treat teams well, invest and strengthen it. The original genius belongs to the families who imagined these Houses.”

Preserving the soul, revealing the beauty

Published by Daphné Segretain